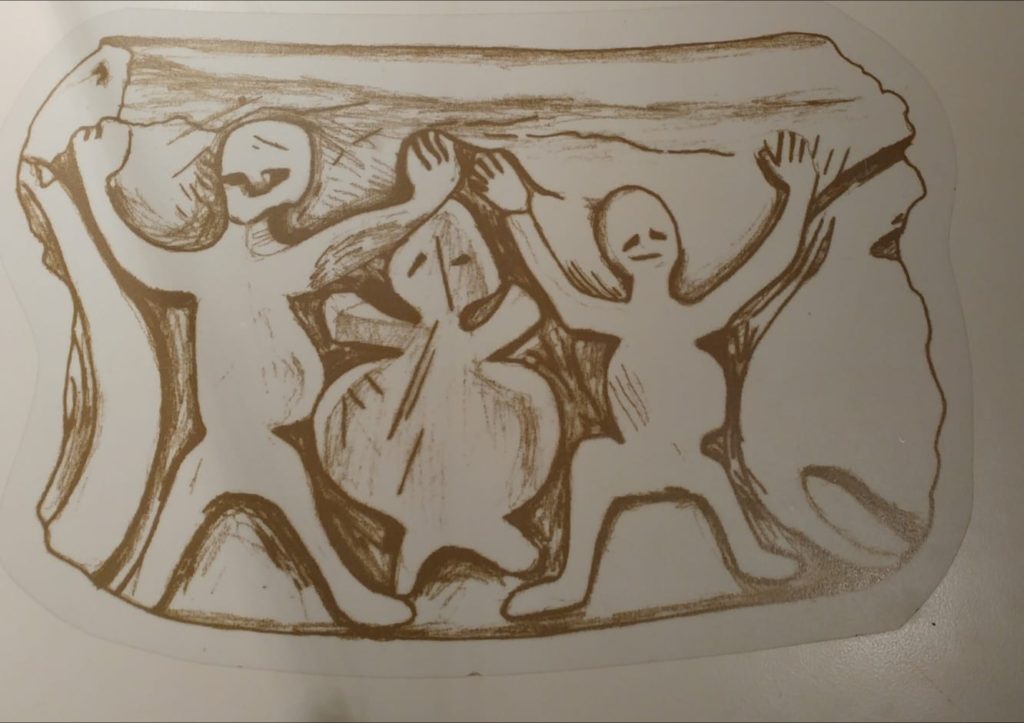

Depiction of bowl showing dancers with turtle from Nevali Çori, possibly showing turtle as a psychopomp or spirit guide of a living person’s soul

Over the past 30 years or so, South East Turkey has been turning into a treasure trove of Neolithic discoveries. From monumental wonders like Göbekli Tepe to little oddities like the stone bowl recovered from Nevali Çori that depicts dancers with turtles, there is a wide range. At first glance this bizarre item has no equivalent. There are carved stone bowls, tanks and cisterns at Göbekli Tepe along with other archaeological sites in the wider region, but there is nothing that is adorned in this manner that has come to light.

The Cult House from Nevali Çori

At first glance it could easily be a simple representation of feasting and dance because from a purely practical point of view, turtles and tortoises are an important food source with very particular advantages. If you flip a turtle onto its back it essentially goes to sleep and can stay that way, in a state of semi hibernation, for months. It’s a source of fresh meat that will keep for a very long time. If you haven’t managed to hunt an auroch, you can come home to a turtle that has been put aside for this very eventuality. There is solid evidence from Clovis sites in Texas that hunter gatherers in North America 12,000 years ago did exactly that and in more recent times sailors faced with long sea voyages under sail, harvested large numbers of turtles for this very purpose from the Galapagos Islands. It’s an ancient and ingenious way of exploiting a food resource and a good idea transcends time and place. But what of the Fertile Crescent region?

The Cult House from Nevali Çori, recovered from site and re-erected in the Archaeological Museum in Urfa

As it happens, not far from Göbekli Tepe, a mere 230 kms away and just east of Diyarbakir at the town of Bismil, the site of Kavuşan Höyük is producing exactly the kind of evidence we are looking for. The site, covers a considerable period of occupation from the last quarter of the third millennium BC to the fourteenth century AD. The particular level which has generated a considerable degree of interest, however, is Level IV which dates to the seventh and sixth century BC. From this post Assyrian period there is a collection of pits for cereal storage and one of these pits has been used for burial. It is of particular interest because this grave, containing the skeletal remains of a carefully placed child and a woman in her mid 40’s, also contains a large assemblage of turtles and tortoises. While turtles and tortoises have been recovered from a number of sites in Iraq and Syria that are clearly matched in age and cultural terms, none quite match the Kavuşan Höyük burial. Placed in the silo with the bodies were a total of 17 turtles along with a tortoise and two terrapins. The turtles are represented by skeletal remains and a plastron (abdominal piece) for each turtle. All carapaces are missing and were removed during slaughter and butchering, presumably for feasting. The tortoise and terrapins are not represented by skeletal remains but only by their carapaces. These are all carefully arranged as part of grave goods or an offering. While a considerable time separates Kavuşan Höyük and Nevali Çori there is clearly a cultural vein that runs through the region with regard to folklore relating to certain reptiles, specifically snakes and, in this instance, turtles. As recently as 40 years ago these skeletal elements from turtles were hung around the necks or shoulders of infants to protect them against the evil eye.

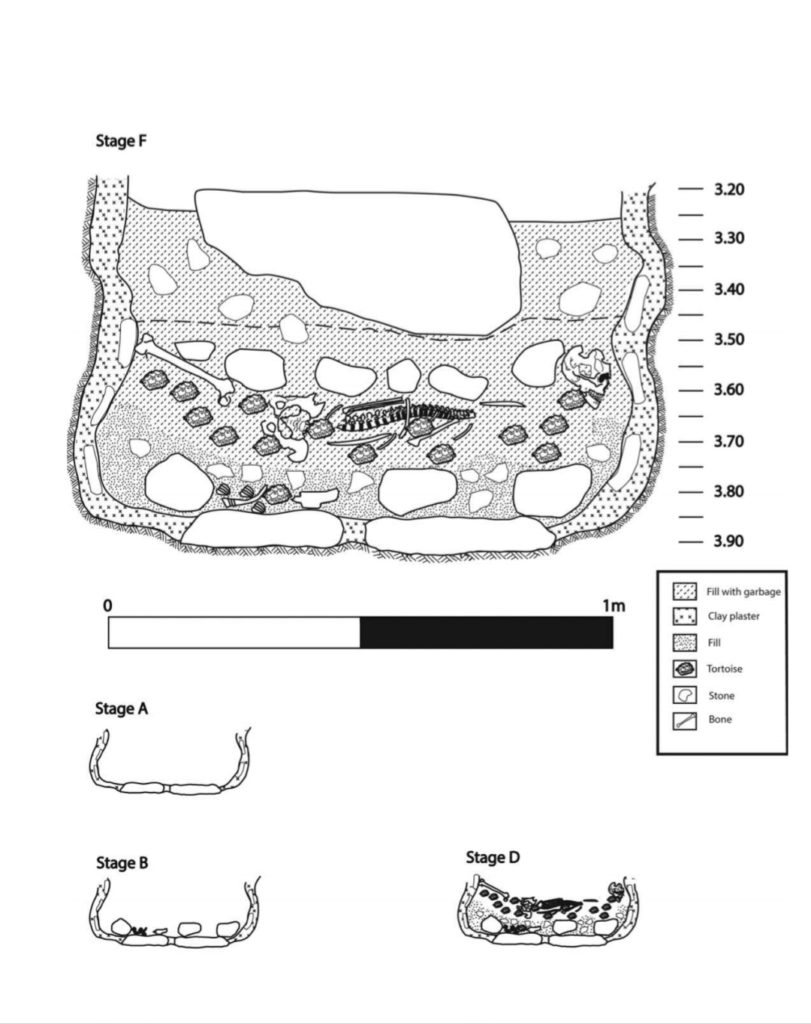

However there are even more powerful indicators of the clearly ritualistic relevance for turtles in the lives of our distant ancestors in northern Israel. West of the northern tip of the Sea of Galilee, is what is thought to be the earliest clear evidence of the ritual burial of a shaman or sorcerer. The site, a cave at Hilazon Tachtit 150 metres up an escarpment, has a number of burials from the Natufian period some 12,000 years before present. What makes this grave site remarkable is a singular ritual internment that acted as the focus for subsequent burials and commemorative activity.

The subject of the burial is female of, for this time, quite advanced age. The individual was about 45 years of age and suffered a number of disabilities that clearly reflect the choice of some of the items placed in the grave with her. People with physical or mental disabilities or who had suffered some kind of trauma were often believed to have a special relationship with the spirit world and would have been able to communicate with supernatural forces on behalf of the community. The woman in the grave at Hilazon Tachtit suffered from a deformed pelvis and, in life, had a “strikingly asymmetrical appearance” which would have caused a pronounced limp as she would have used a twisted gait dragging her foot as she walked.

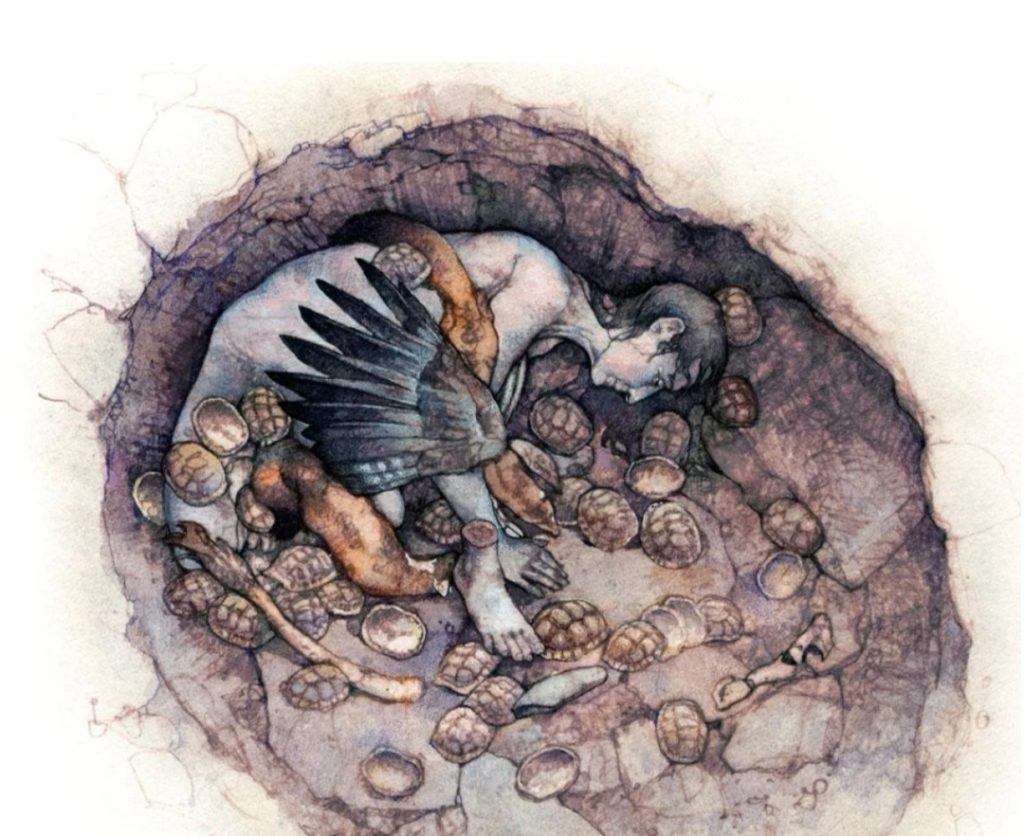

The funerary feast included roasted tortoises and their blackened shells were placed around her. Some of the tortoise shells were tucked under her head and hips while shells were piled on top and around her body. They then, carefully placed over her the wing of an eagle and up against her body the pelvis of a leopard and, rather disturbingly, the severed foot of a human being! In the world of the spirits she was to be unencumbered by the disabilities she carried in life.

Hilazon Tachtit – Shaman burial, artist’s impression

Hilazon Tachtit – archaeological diagram

In the years following her burial, members of this community made the trek up to her resting place in this remote cave to bring more bodies for burial and, as evidence of feasting demonstrates, to commemorate their ancestors. At least 27 subsequent internments have been identified. In later visits, people reopened communal graves and removed defleshed body parts, including skulls for burial elsewhere or possibly for display. The practice of displaying skulls decorated with plaster “flesh” is known from Jericho as well as from the later site of Çatalhöyük in the Konya Plain. Çatalhöyük in particular, has yielded ample evidence of ancestor worship based on close proximity to the dead and the display of skulls. There is now good evidence for a “skull cult” at Göbekli Tepe.

In the case of Hilazon Tachtit, the burial cave was clearly a place of ritual, communal activity surrounding the process of death and remembrance which performed the same function at around the same time that Göbekli Tepe was starting its period of use. The recent evidence of a skull cult at Göbekli Tepe, which although shows some specific characteristics, also makes the case for a shared cultural milieu across this wider region, from modern Israel, up through Syria, across South and South eastern Turkey and into Iraq.

Feasting at Göbekli Tepe, like at Hilazon Tachtit was periodic and involved the consumption of quantities and species of animals not usually a component of daily diets. However, at a time when people were making the transition from pure hunter gatherer society to more settled and sedentary life with bigger communities and growing use of domesticated varieties of plants and the eventual domestication of animals, communal activities were the essential glue to establish common identity, shared values, cultural continuity, resolving disputes and mixing genes. At Göbekli Tepe we are seeing the evolution of a complex culture based around communal activity with extensive feasting demonstrated by the provision of animal bones mixed in with the spoil used to back fill the enclosure. We’re also seeing at Göbekli Tepe, at Level II, a clear cultural change indicating a more advanced degree of the managed use of plant resources. While the Level II enclosures are simpler, smaller and more rudimentary, there is now some evidence gathered from stone carved tanks, for the brewing of alcohol, as well as stone vessels and tools for the processing of grains. The evidence from dozens of sites across the region is for interconnected cultures in the process of a great transition, rather than the revolution that had been part of the accepted view until now, Revolutions are sudden, while what we see with the transitions emerging here is the culmination of a long process taking thousands of years. Sites like Göbekli Tepe, Nevali Çori, Karahan Tepe and then South to Jerf el Ahmar in Syria then Hilazon Tachtit and Jericho in Israel are the last flowerings of the complex and intriguing Stone Age.

Which brings us back to our exuberant dance scene at Nevali Çori. Of course, we can never really know for sure, but it seems to tap into many elements that run through life in the region through time, occasionally surfacing to tantalise the modern observer. So, our stone turtle dancers from Nevali Çori, a shamanistic dance in altered states of consciousness with mystical turtle beings in a celebration of life and death, or just dinner?

To visit Göbekli Tepe and Urfa:

For further information:

“The role of cult or feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities. New evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey.

Oliver Dietrich, Manfred Heun, Jens Notroff, Klaus Schmidt, Martin Zarnkow

Modified human crania from Göbekli Tepe provide evidence for a new form of Neolithic skull cult.

Julia Gresky, Juliane Haelin, Lee Clare.

Buried with turtles; the symbolic role of the Euphrates soft- shelled turtle in Mesopotamia.

Remi Berthon, Yılmas S. Erdal, Marjan Mashkour

A Natufian Ritual Event

Leore Grosman, Natalie D. Munroe