“The Stone Age didn’t end because they ran out of stones” Ahmed Zaki Yamani 1930- 2021

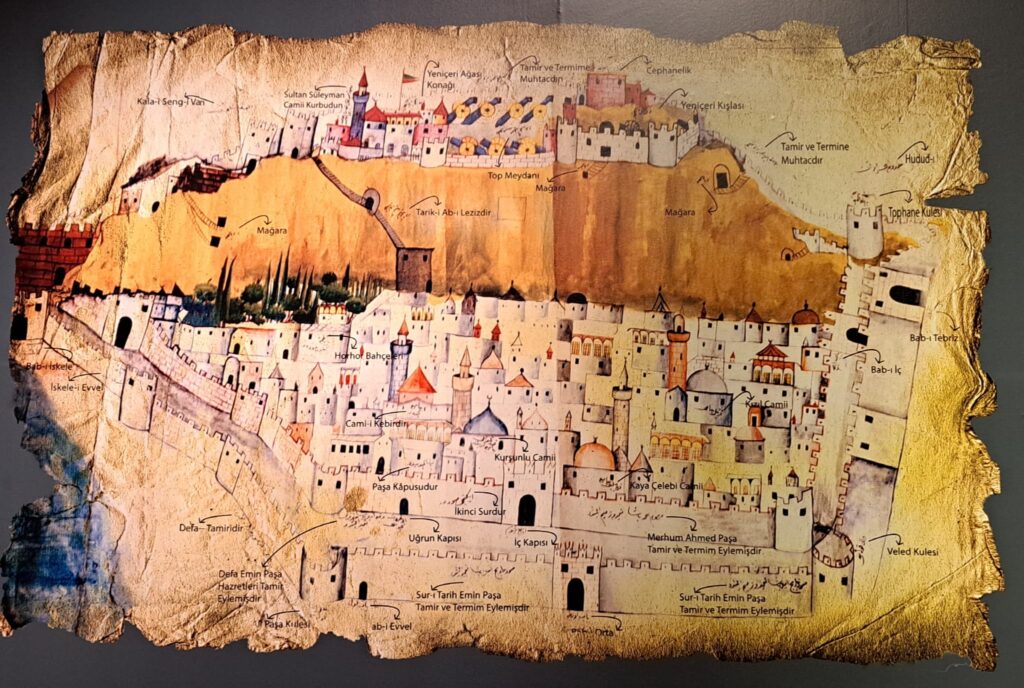

The Eastern Anatolian region, centred around Van, has a long history that is reflected in the city’s new, recently opened museum which is located adjacent to Van Citadel on the shores of the eponymous Lake and we have been waiting for this museum for years. Delays in planning, delays in design, delays in construction and then….Covid. But finally, it is here! And it’s not just here but it’s a tour de force..

From the Stone Age to the present, few places can boast such well established and uninterrupted record of human life and cultural development. In fact, Van Citadel was established by the Urartian King Sarduri I around 839 BC. It has been used almost continuously ever since, last seeing action just after WWI. I think it’s unlikely that any other fortress in the world can match this 2800 plus year history.

Some extra reading…

The area encompassed by the province of Van has acted like the hub of a great wheel not just spinning off diverse cultures and civilisations as they came through but also being the birth place and home of unique cultures too. This treasure trove of humanity is beautifully represented and displayed in Van’s new museum; both the Urartian castle and museum can be covered in a day and I would suggest that few places anywhere will allow the visitor to see and get close to such an extended and unbroken line of human history.

Article continued below…

The museum is laid out to lead you through Van’s amazing time line starting with a wall explaining the march of time before directing you off through the various exhibition rooms. I will cover the museum by highlighting specific objects or groups of objects or themes. There is so much that one needs to narrow things down.

The Obsidian “Knob”

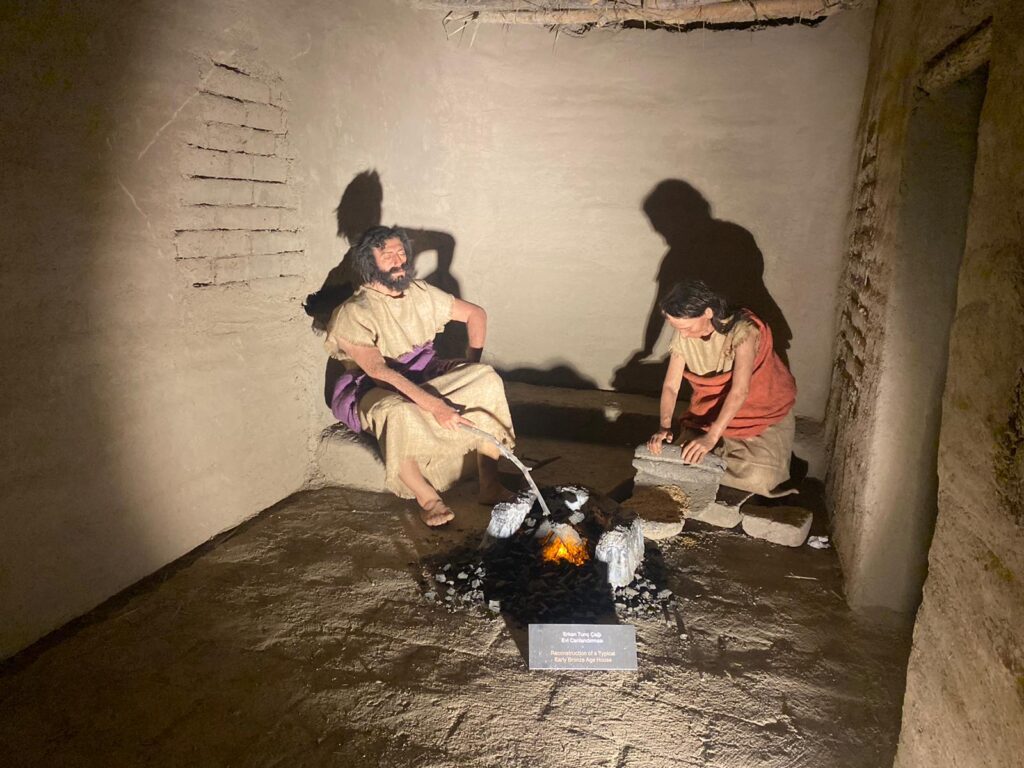

The first galleries cover eastern Anatolia’s Stone Age and Chalcolithic periods which are dominated by stone artefacts and tools and by early copper technology. These rooms, I noticed, are covered quickly by the museum’s visitors because most people are after the “spectacular.”

However, for me, this section has one of the most astonishing objects in the entire collection. If you’re in a hurry, you miss it, but, in a dimly lit gallery there is one display case that has a wonderful array of obsidian tools made with real skill and artistry. However, there is one item in the case that appears to have defied labelling or explanation. The Card simple says “Obsidian Knob, Obsidian, Tilkitepe Mound, Chalcolithic period.” And this is literally what it is. But what exactly? And why? The object looks, in shape and in size, very much like a 6 inch artillery shell, but a dull black. It’s clearly hand made but to make an object this shape in obsidian, a volcanic rock that likes to fracture along set, internal planes, is really difficult.

Article continued below…

The age of these obsidian artefacts are also indicative of the fact that there is considerable overlap between the “Ages” historians apply to the flow of history which is both interesting and instructive. The Obsidian Knob comes from the Chalcolithic Period/Age but clearly, stone blades and other objects are still in use and this is the point. What the “knob” actually is, is an obsidian core from which individual pieces are struck off in order to manufacture specific blades and tools. Obsidian continued to be used well into the Chalcolithic (Copper) Age because it produces consistently sharp edges that copper blades could not match. This brings to mind the great observation made by the 1970’s Saudi Oil Minister, Sheik Yamani: “Remember, the Stone Age didn’t end because they ran out of stones.” Technologies and Epochs overlap.

Flint and obsidian tools demonstrate human ingenuity and skill and show how people can do amazing things with not very much. Obsidian dominates the Stone assembly here because, in this volcanic region, it is abundant. In fact, obsidian was a part of a trade network stretching hundreds of kilometres way back into the Neolithic. Obsidian blades from the Lake Van area have been identified at the Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe and in the wider Taştepeler area, stretching down into northern Syria and Iraq.

Article continued below…

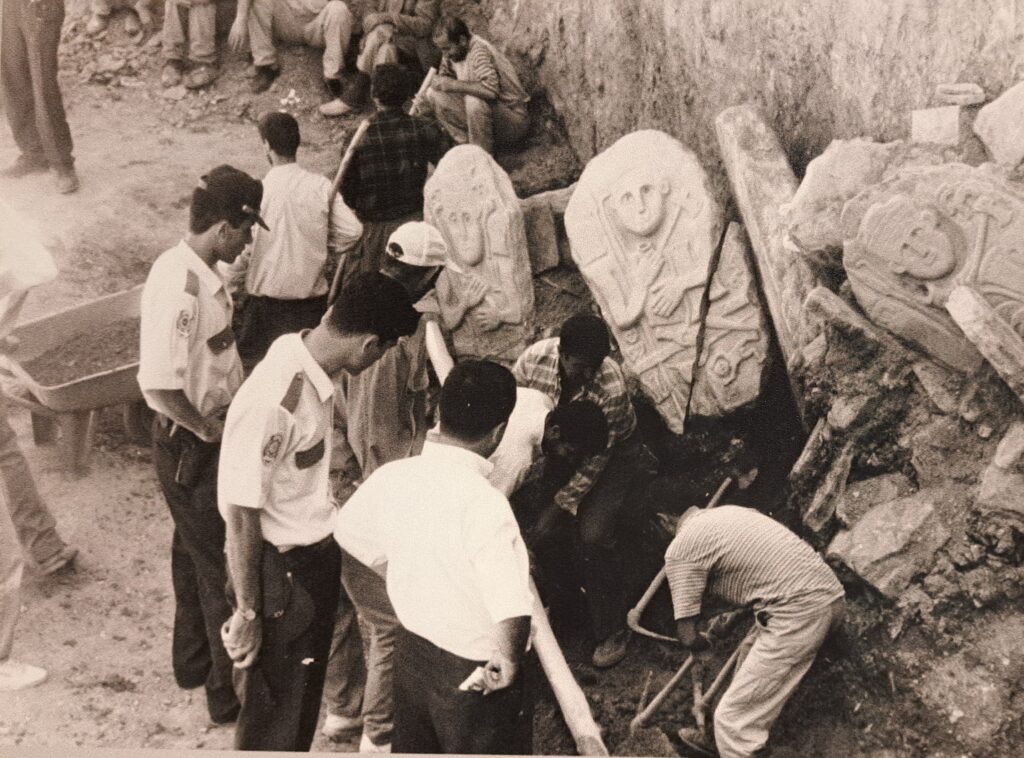

The Hakkari Stelae: a connection with Central Asia

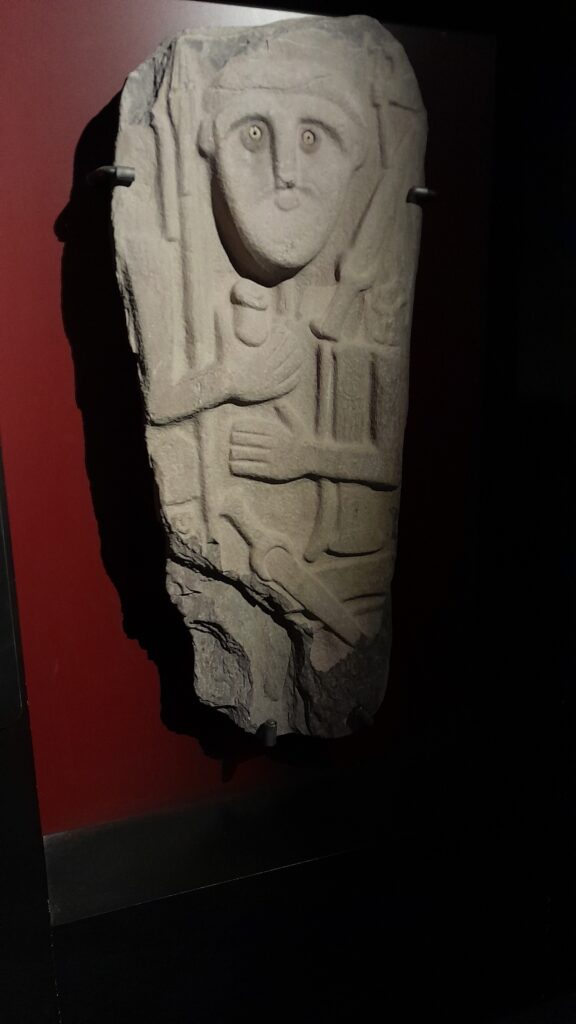

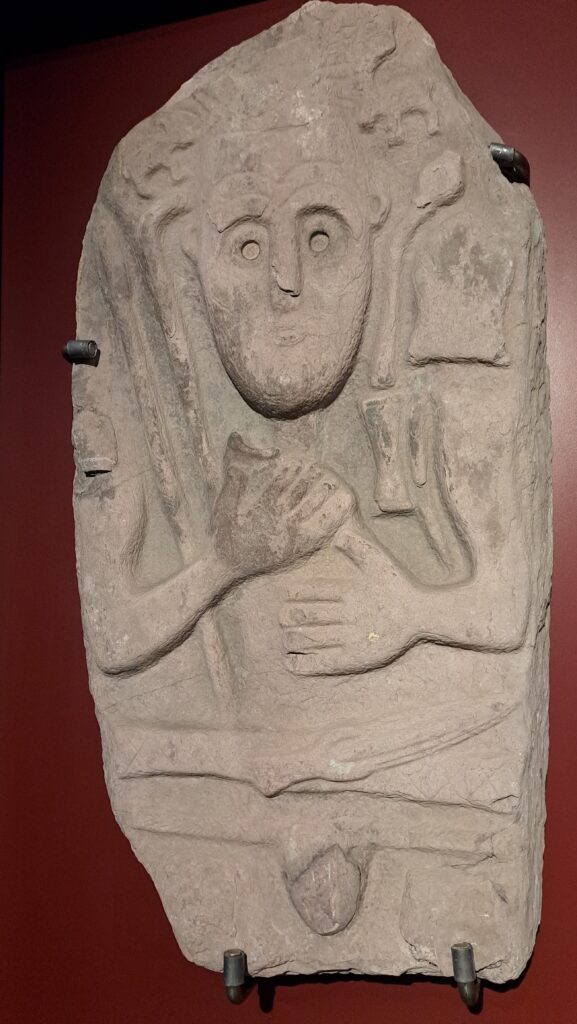

The thirteen stelae, discovered in a group in 1998 in Hakkari Province just South of Van are comprised of eleven men and two women.

They are of varying sizes, roughly shaped in outline and were set in gravel, probably upright in a group, but found leaning backwards. Within the composition of the figures are depictions of possessions and events that appear to be indicative of the status, wealth and achievement of the person represented. In the case of the males they are clearly warriors with various weapons shown, ingots possibly illustrating wealth, animals, females or slain enemies. The two females figures are smaller, represented in softer outline and without possessions or a “history” marking out status but it is clear that their inclusion in the group makes them special. The Stelae vary in size from about 1.3 metres to just under 2 metres.

The depiction of Yurt type tents on several stelae indicates the nomadic or semi nomadic nature of a culture that lived across this rugged landscape. The metal ingots suggest enrichment through trade or metal working associations while the weapons suggest a type that can be dated to 15th – 13th centuries BC. They are the westernmost representation of a monumental tradition that stretches east into Central Asia. The chosen location of the Hakkari Stelae is interesting in that they were positioned adjacent to a Chamber Tomb containing the remains of seventy five individuals that can be dated to about two centuries prior to the erection of the first Stelae.

Urartu

Artefacts from the Kingdom of Urartu are the most spectacular in the museum. We now go from preliterate and consequently ambiguous and enigmatic cultures where symbology was the primary “written” means of transmitting information, to a literate society that begins to intersect with Western civilisation in a way that is slightly more familiar.

Article continued below…

This is the kingdom referred to in the Bible as Ararat, an indigenous people existing as a powerful and independent state covering what is now Eastern Turkey, North Western Iran, Armenia and parts of Azerbaijan and Georgia between about 860 BC and 590 BC. Eventually succumbing to invaders they, nonetheless, left behind a rich legacy of gold and silver work along with many examples of extraordinary bronze work and superb carving in Stone. Their use of bronze extended well into the iron age, another example of technology overlap. Technologies and Epochs overlap.

They were also known as master horsemen and charioteers, military engineers and water managers of some genius: the water system built by the Urartians still supplied Van with water right up until the 1960’s when the city’s population finally expanded beyond its capacity.

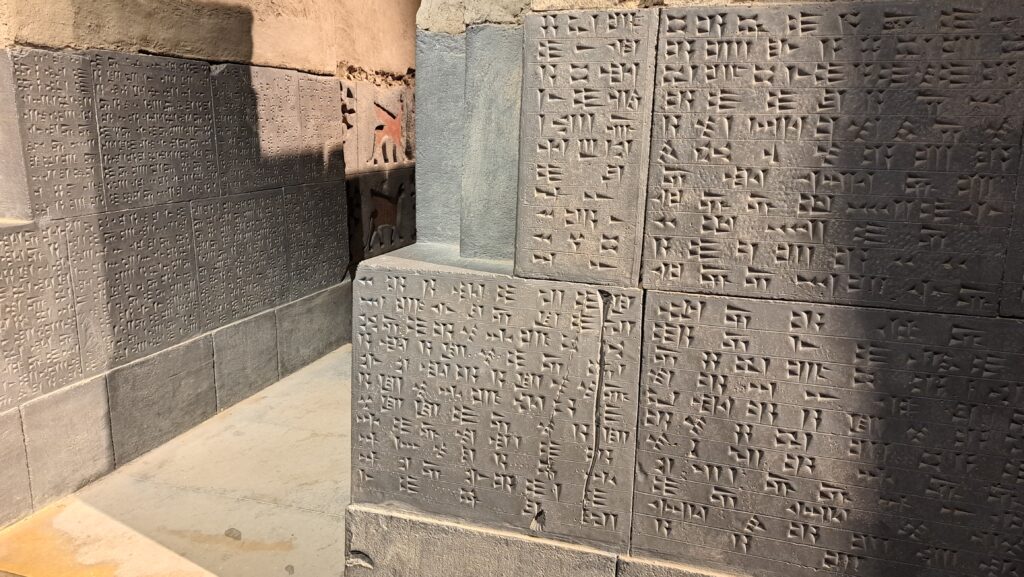

Artefacts from the Fortress of Ayanis Urartian fortress located North of Van and on the shore of Lake Van, and the temple on the peak of the citadel is dedicated to the premier Urartian, God Haldi.

Article continued below…

The temple, which was one of the holiest places for the Urartians, remains intact, as does the temple’s podium hall and the extraordinary stonework with which it was adorned. The excavation team is replacing the engraved stones in their original place in the Haldi Temple.

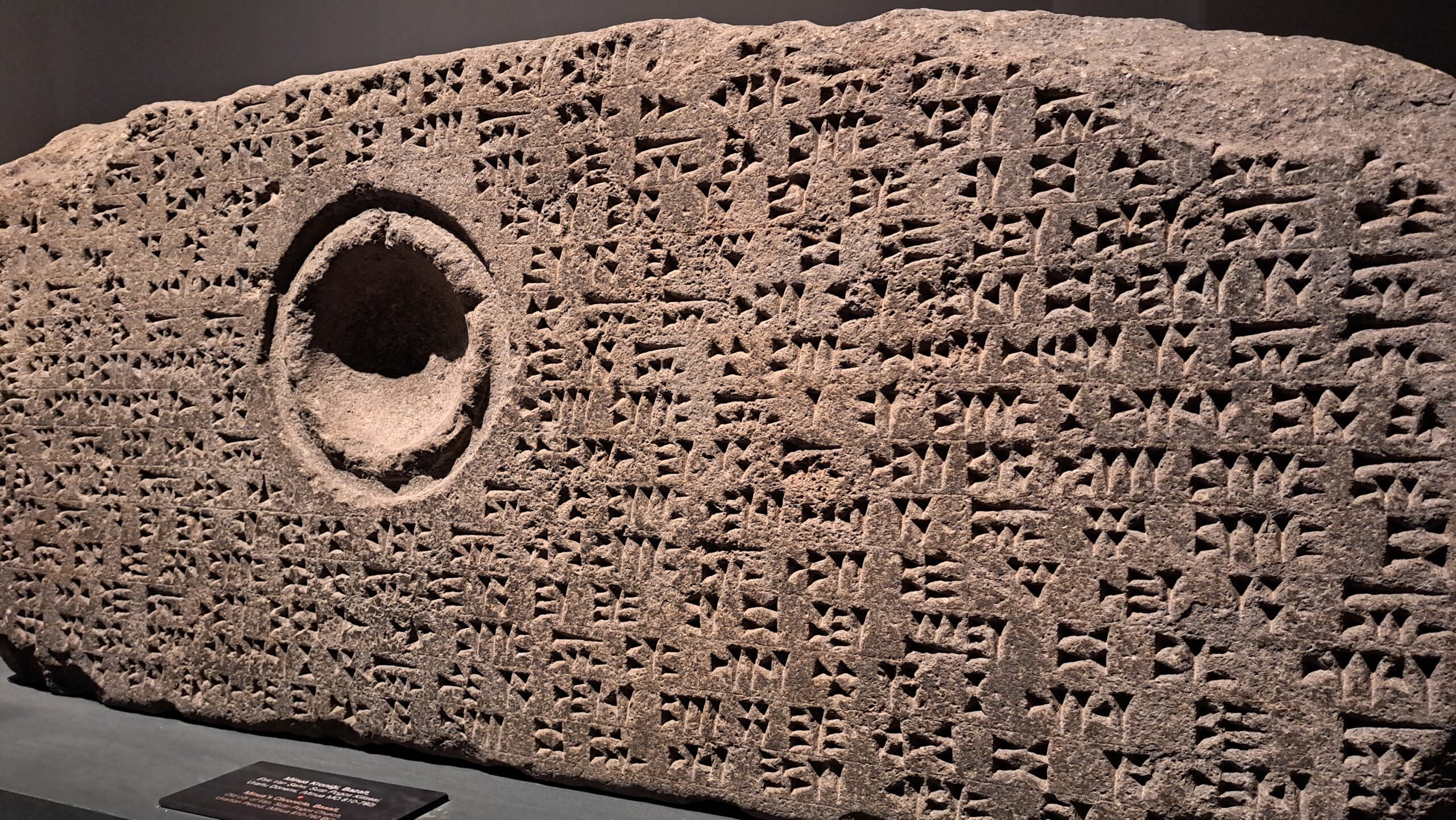

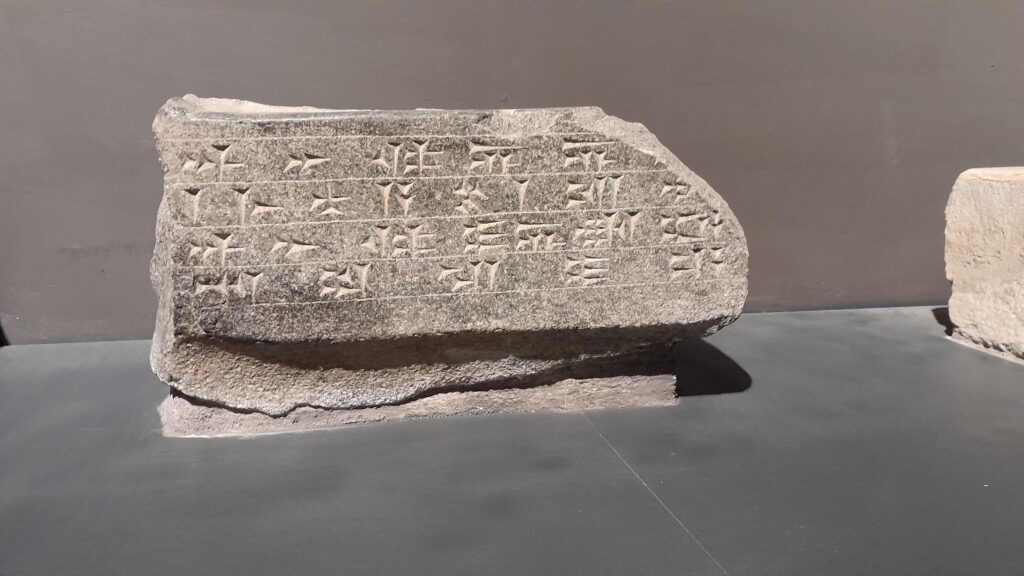

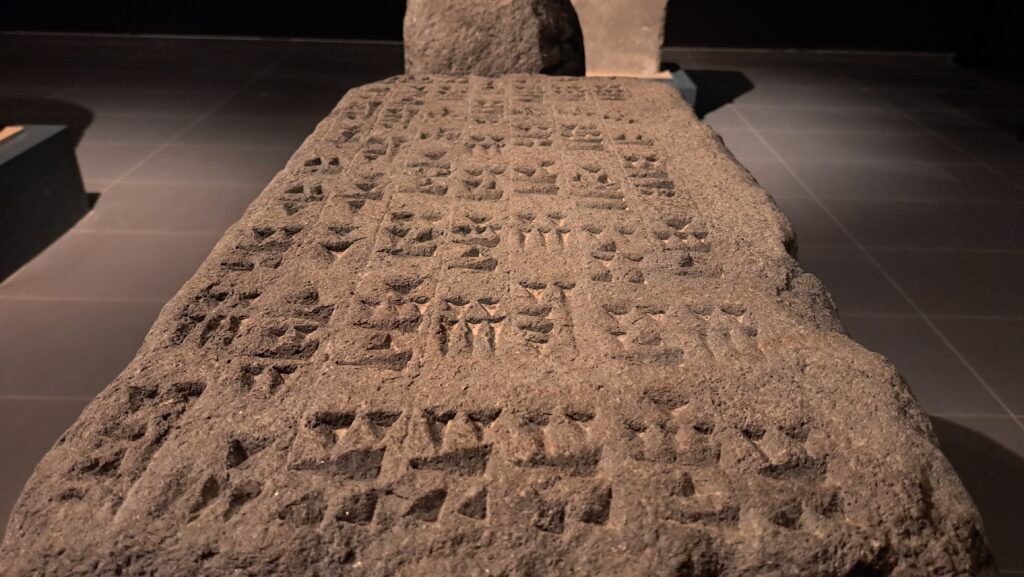

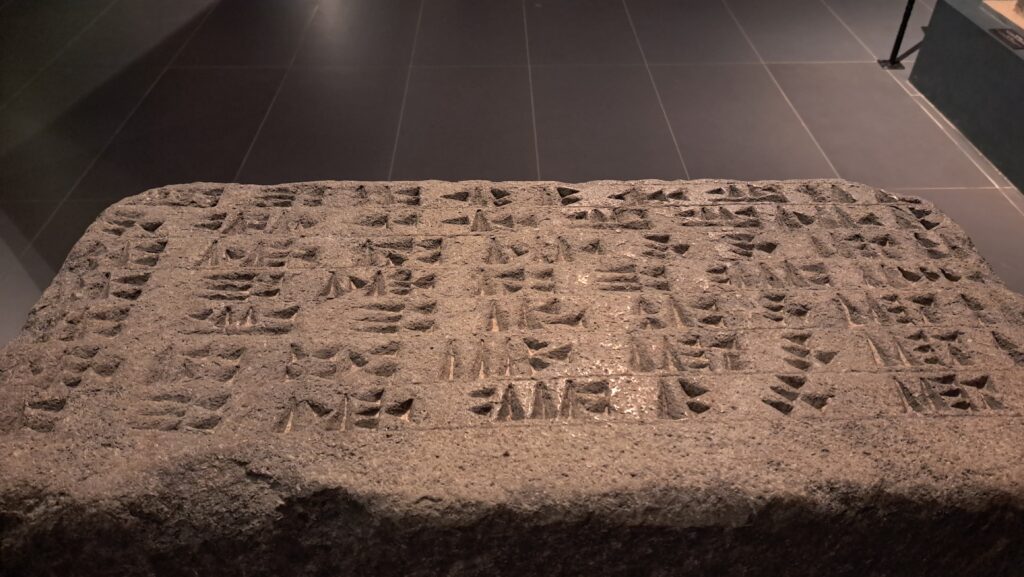

Built by King Rusa II, son of Argishti, (685 to 645 BC) the structure is in excellent condition and even survived the dreadful earthquake of 2011. On the front side of the temple, and along the short access passage to the inner sanctum carved onto eight large basalt blocks can be seen a temple inscription, carved in cuneiform script, the dedication of the temple in what is the longest inscription from Urartu yet discovered.

The fortress will be roofed over and open as a museum but key artefacts, among them a helmet, shield and the Sacred Spear of Haldı which represent the pick of artefacts are located next to the Temple of Haldi reconstructed in the museum.

They represent the apogee of the Bronze maker’s art and are in an extraordınary state of preservation. These are significant artefacts as the God Haldi was the primary deity of Urartu and also the God of War.

Chariots

The people of Urartu were master horsemen and skilled charioteers and one room is dedicated to this aspect of Urartian civilisation with fascinating displays of finely worked bronze horse and chariot equipment along with weapons and armour. Just outside Van is the fortress of Upper Anzaf which has various irregular and circular shapes carved into the bedrock and which for years defied explanation.

However, looking at the collection of shapes in their entirety, it dawned on archaeologist Erkan Konyar that the shapes described in the rock were the shapes of chariot components from wheels to carriage sections. Their purpose is basically to hold wood, softened by water and heat in the desired shapes. Wheels, in this instance, are made by softening lengths of wood in steam or boiling water until they are pliable, then bending them into these stone carved shapes. When the wood dries and cools it retains the new shape and can then be banded with an iron or bronze rim for strength, Other carriage components can be shaped in the same way. The product of this fascinating technology is explained here.

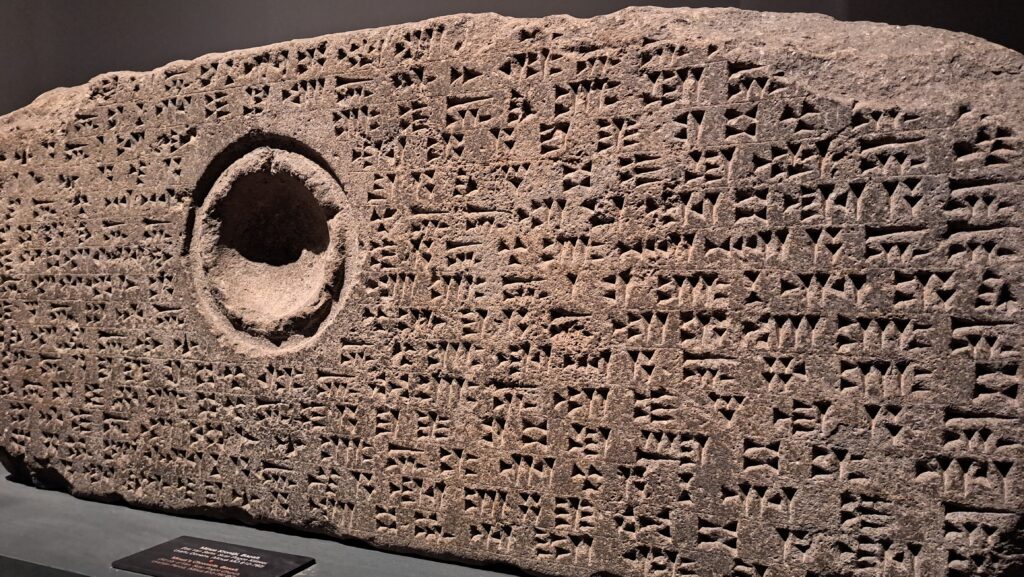

The enigma of Cuneiform

Cuneiform was the first formal writing system and was developed in Mesopotamia. It appears to be fiendishly difficult and was lost to history early in the modern era, being supplanted by Greek and Roman lettering. Consequently, the history of our development as civilisations in the west has been skewed by the complete absence of the memory of its origins in the Mesopotamian and Anatolian regions.

It was not until the 19th century that European scholars rediscovered Cuneiform, deciphered many of the languages and were able to explore the rich history of our ancient origins. That said, this part of our collective heritage remains unfamiliar to most and some of the joys of travelling in Turkey west of Ankara is the thrill of being able to rediscover this missing history in what is the safety of a secure country that is actually familiar to most of us. This part is new and it’s just a step away from the holiday beach we enjoyed last year.

The first reference to Urartu was from the Assyrians, modern day Iraq, and an inscription of Sarduri I, written in the Assyrian language. Subsequently. his son Ishpuini (830–810 B.C.) and later rulers all wrote in the Urartian language (a language isolate related to Hurrian, another language not related to other regional languages). Very few examples of writing exist on clay tablets, but there are about 500 rock-cut inscriptions found throughout Urartu, as well as inscriptions on hundreds of objects and memorial or religious stelae. They record military campaigns, religious rituals, the names of the many deities in the Urartian pantheon, and dedications to public works relating to agriculture, civic building, and waterworks. Many of these stelae are collected in this museum.

The Kingdom of Urartu collapsed suddenly with the precise cause or its perpetrators uncertain but possible culprits include the Medes or incoming nomadic groups such as the Scythians. Little was left but archaeology is gradually picking through the sites and artefacts that have survived looters through the centuries and has been piecing the culture back together; the many cuneiform inscriptions you see in the museum are part of that emerging and rediscovered story. From Urartu the museum traces the regional historical record through Persia. Turkic, Armenian Ottoman and modern periods but it’s Urartu that holds the visitor’s focus.

Article continued below…

Thank you very much for reading our latest travel journal. We really enjoyed this museum, in fact, we enjoyed it so much, we went back again the next day to soak it all up again. We learnt a lot and we hope you did too. Nick and Sally