There are parts of the world where the mystical and sacred intersect with the mundane and profane, which gently exhale a sacred breath and while they attract veneration and respect from different peoples and cultures through time, they quietly endure. Anatolia, especially south east Anatolia, is such a place. Its subtle, sometimes barely visible, network of myth, legend, faith and sanctity goes back to the dawn of time before agriculture, before writing and before bread and it’s not until you disturb the dust of today that you start to see the deep roots of this place and the amazing antiquity of what is here. It is not just the stunning sites of Göbekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe or the other sites now emerging in the Tas Tepeler region and which go back 12,000 years or more.

You can find one here, outside the ancient city of Mardin, hidden beneath the Syriac Monastery of Deyrul Zafaran, also known as the Saffron Monastery. As Christianity expanded and supplanted the old religions, it took on the sacred sites of ancient custom and veneration. The Monastery is located on the site of a temple dedicated to the Mesopotamian sun god Shamash, which was then converted into a citadel by the Romans. After the Romans withdrew from the fortress, Syriac Christians transformed it into a monastery in 493 AD, but an important part of the temple remains.

Shamash, sometimes known as Utu, was believed to see everything that happened in the world every day. Because he saw everything he was considered responsible for justice and the protection of travellers. As a divine judge, he was also associated with the underworld.

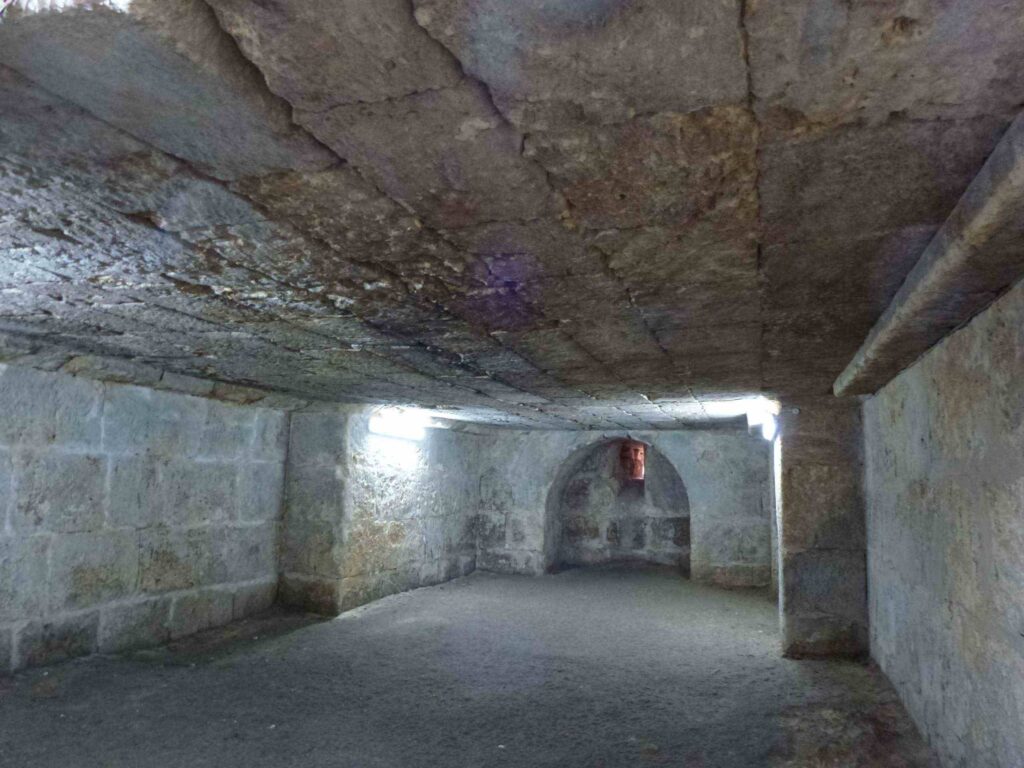

To reach the temple, one descends beneath the monastery building into what looks at first glance to be a cave or cellar with a low stone block ceiling. This is the oldest part of the structure here today and it goes back possibly as far as 1,000 BC.

Article continued below…..

The faithful Sun worshippers were known as Shamsi or Shamasi, and followed a monolatric path. In other words, while they accepted the existence of many Gods, they acknowledged the primacy of one and worshipped that God alone.

The space that is the temple is disturbingly low and there is an unsettling sagging bulge along the ceiling’s centre line. However it has been there for at least 3000 years, and with about 3 metres of soil, compacted overburden and then the monastery building itself above, it is safe to assume that the structure is sound.

The secret, which you will only see as you descend the stairs and turn to enter the space can be observed in the structure of the ceiling. It is all held up by what is called a Jack Arch. Unlike regular arches, jack arches are not semi-circular in form. Instead, they are flat in profile and while they work to the same principles as a regular arch, are used in the same way lintels are used.

Unlike lintels, which are subject to bending stress, jack arches are composed of individual masonry elements cut or formed into a wedge shape that use the compressive strength of the masonry and supports on either side. Like regular arches, jack arches require a mass of masonry on either side to absorb the considerable lateral thrust created by the arch. They look wrong, but with the side supports they are very strong and this Temple to Shamash, is supported on either side by the earth itself and is oriented to the east and the rising God himself.

The chamber has a window to the outside wall facing eastward, where the sun rises and would prompt the Shamsi to begin their daily ritual as the God’s first rays broke the horizon and flooded the chamber with light.

Article continued below….

But what of Shamash, or Utu? While the Shamsi worshipped Him alone, in the broader context Shamash was a personality in a Mesopotamian and Anatolian Pantheon populated with many Gods taking many forms and names. There are no known myths focusing on Him alone, but clearly He is important. He often appears in other myths as an agent of important events or as an ally of other figures in both Sumerian and Akkadian compositions. For example, in various versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh and in earlier Gilgamesh myths, he helps the eponymous hero defeat the monstrous Humbaba.

In the myth “Inanna and An”, he helps his sister, Inanna, acquire the temple of Eanna. Located in Uruk and known as “The house of Heaven” Eanna was the earthy residence of Inanna and An. Inanna is an important figure. She has a wide and encompassing portfolio in the Pantheon of Mesopotamian Deities as the Goddess of love, beauty, war, and fertility.

She is also associated with Divine Law, sex and political power, an intriguing and potent combination. Originally worshiped in Sumer as Inanna, but later on as Ishtar by the Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians, she features in the Hittite Rock Sanctuary of Yazilikaya as Ishtar and Venus.

There is an intriguing link with the prehistory of this area in Shamash’s enabling role in the story “How Grain Came to Sumer”, where he is invoked to advise the divine brothers Ninazu and Ninmada. Ninazu was a Sumerian god of the underworld. He was also associated with snakes and vegetation, and with time acquired the character of a warrior god. The god Ninmada, was also associated with snakes and was called the “snake charmer of An”. The God was incarnated with both Female and Male personalities. The female Ninmada was a divine snake charmer, the male Ninmada was called the “worshiper of An” and was regarded as a brother of the snake god Ninazu. However, in the myth “How grain came to Sumer” the brothers gift grain and flax to mankind. The story says:

“Men used to eat grass with their mouths like sheep. In those times, they did not know grain, barley or flax. An brought these down from the interior of heaven. An piled up the barley, gave it to the mountain. He piled up the bounty of the Land, gave the innuha barley to the mountain……… Let us go to the mountain, to the mountain where barley and flax grow; …… the rolling river, where the water wells up from the earth. Let us fetch the barley down from its mountain, let us introduce the innuha barley into Sumer. Let us make barley known in Sumer, which knows no barley.”

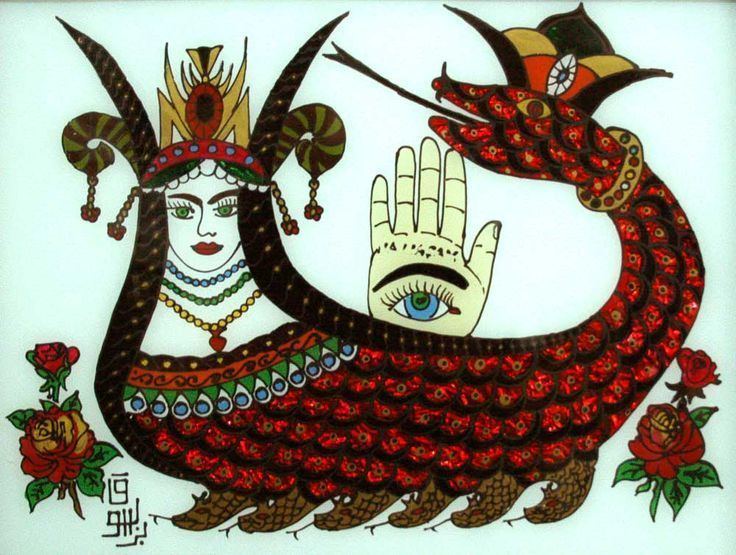

What we have here is a vibrant, if often confusing, complex corpus of mythology and legend that invokes prehistory in this region, long before literacy was known and created as a repository of culture. Not far from Mardin to the North West is Karacadağ where the first domesticated wheat emerges from its wild form, einkhorn. Also to the West are the Taş Tepeler Neolithic sites featuring among them Göbekli Tepe with its profusion of snake imagery. Emerging out of all of this is the Shamaran, half human, half snake, and a visible presence in the lives of people to this day. Enter a shop or a home and you will see an image of the Shamaran as a protector and guide of people living or working there.

The Shahmaran’s current incarnation is as a mythical and mystical half-woman and half-snake living in a mysterious subterranean garden. Many versions of her have been featured in various legends and the stories are to be found across different cultures from Turkey to Syria, Iraq, Iran, the Caucuses and into Central Asia.

The story of the Shamaran, and her message, is about love, betrayal, forgiveness and faith but it’s also a warning against the perils of greed.

For fans of fantasy drama, check out the new Netflix series Shahmaran, we’ve put the links here for you.

From Sun Temples to Mystical Gods and Beyond. Your next adventure is waiting for you. Thank you for reading our travel journal. We would love to hear from you if you have experiences of this amazing place or you would like to find out more or book your next holiday with us. Come to Turkey, the birthplace of agriculture and where bread is BIG 🙂 Sally and Nick.

Treasures of Eastern Turkey – Turkey Tour Agency (easternturkeytour.org)

What is the Silk Road – The Silk Road across Turkey (easternturkeytour.org)

Eastern Turkey Excursions – The Grand Tour of Eastern Turkey (easternturkeytour.org)