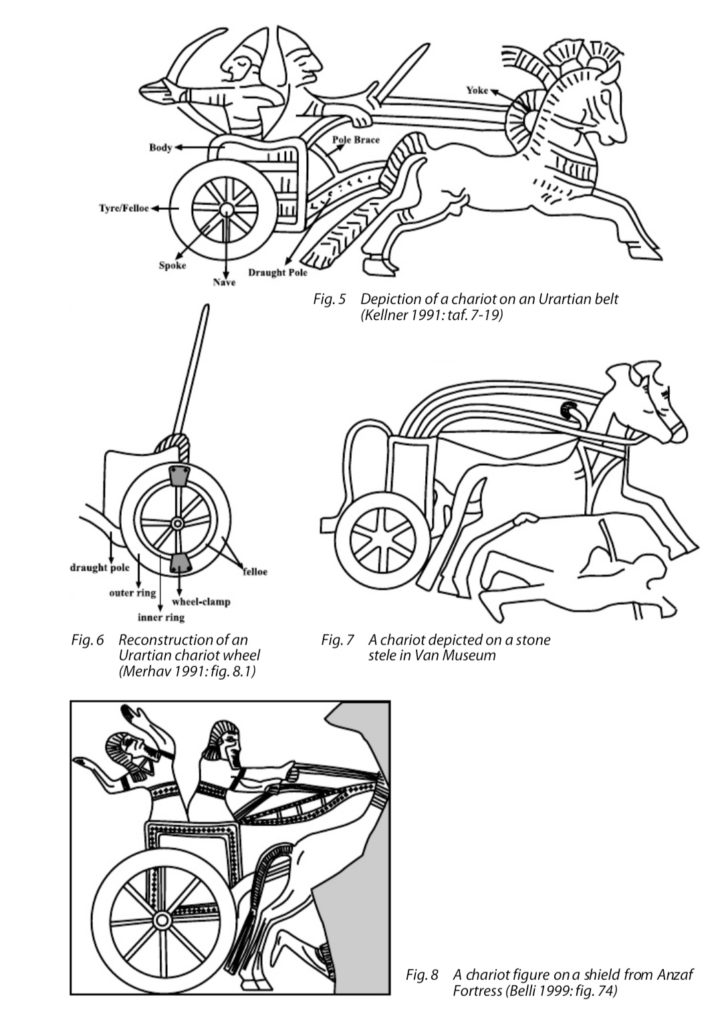

Upper Anzaf Fortress, 10 km just east of Van is a curious place. At first glance there’s not a lot to see. Just the remnants of a long stone wall skirting the hill. They could be old but they could be young. However, on closer examination they turn out to be the foundation of an extensive defensive wall ringing the hill. As it happens Upper Anzaf is ancient. It dates back to the 8th century BC and was constructed by the Urartians, an enigmatic people native to these east Anatolian Highlands. They were a unique linguistic group that established an empire, based in Van, that took in Eastern Anatolia, Armenia and North West Iran. Their land is mentioned in the Bible as the Land of Ararat. They were renowned for their military architecture, inventive use of water supply and, mostly, breeders of horses and as charioteers of excellence. It’s in this last capacity that their work at Anzaf becomes important. Below the curtain wall, on the lower slopes of the hill, are a series of enigmatic and puzzling rock carvings.

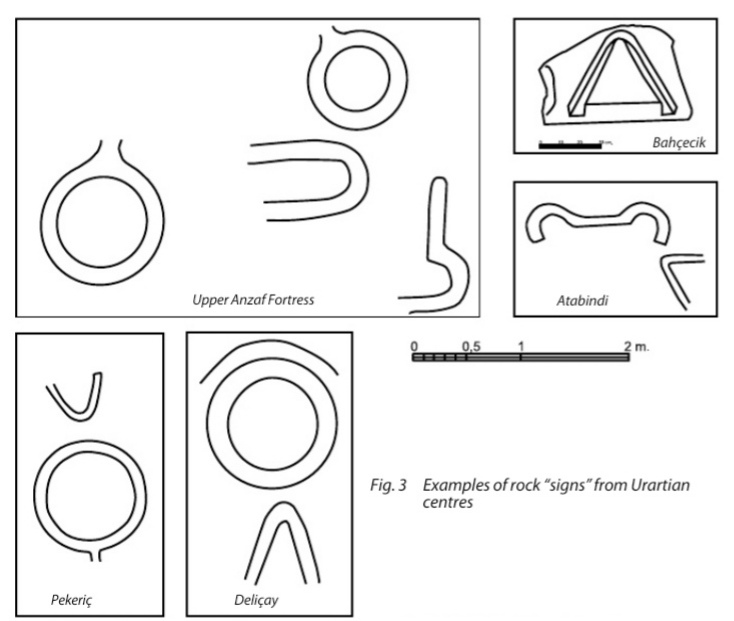

These deeply cut shapes are circles and curves. Initially archaeologists interpreted them as symbolic, unable to assign to them any practical purpose. But in 2006, Turkish archaeologist, Erkan Konyar solved the enigma in an important paper, “An Ethno-Archaeological Approach

to the “Monumental Rock Signs”

in Eastern Anatolia”.

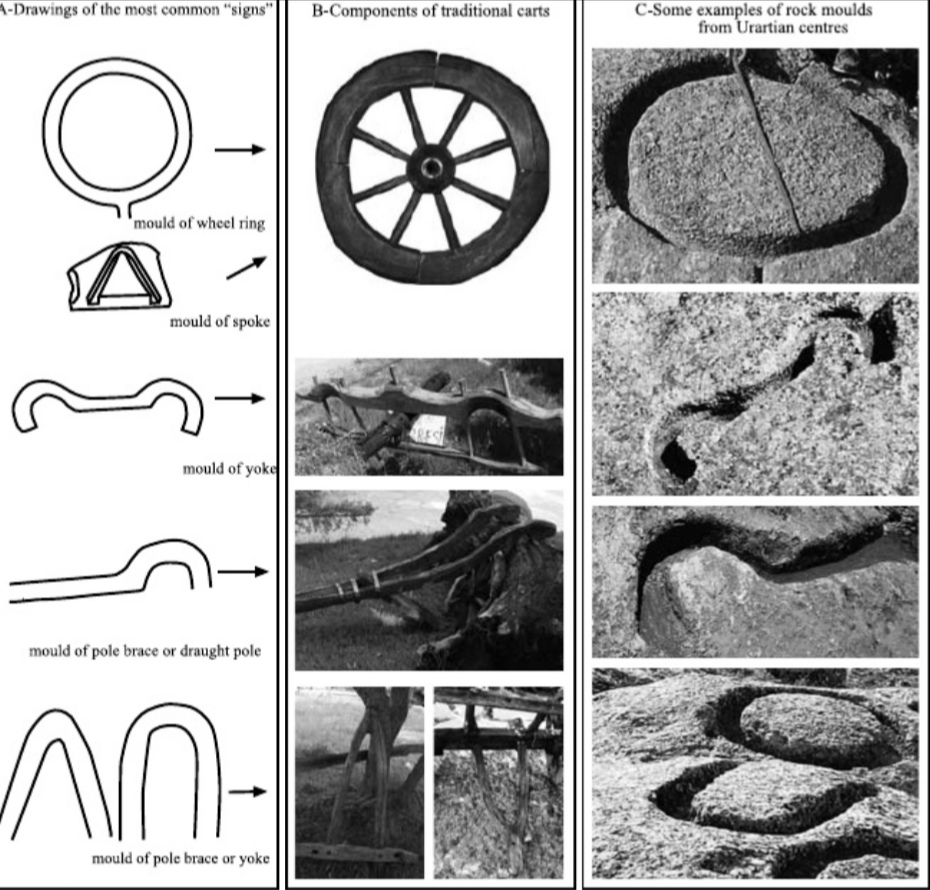

Rarely visited, protected by the fierce kangal dogs of local farmers and definitely off the beaten track, the Anzaf rock carvings are, in fact, moulds that the charioteers of ancient Urartu used to make the wheels and components for their chariots.

The moulds were used to shape the wheels and sections made from wood. The technique, though requiring great skill to execute, is simple in concept. It’s still used today by skilled carpenters, wheel wrights and bow makers. They carefully selected sections of wood, boiled or steamed them to make them pliable and then bent into the mould where they expanded out to fit the shape. Once cooled and dried they retained their moulded shape. They were then banded with metal hoops producing solid but flexible wheels. Various components of the cart were formed in the same way.

As Konyar points out the shapes closely coincide with what we know about Urartian chariot design and are to be found at a few other locations, but the examples at Upper Anzaf are particularly fine. Konyar concludes by observing that “the technique of shaping timbers in moulds requires convenient forests and tree types. The fact that the “signs” occur only in the Urartian realm can explain this phenomenon.

Although other Near Eastern powers such as the Assyrians and the Late Hittite Kingdoms did possess considerable numbers of chariots, this technique seems to be peculiar to the Urartians. “